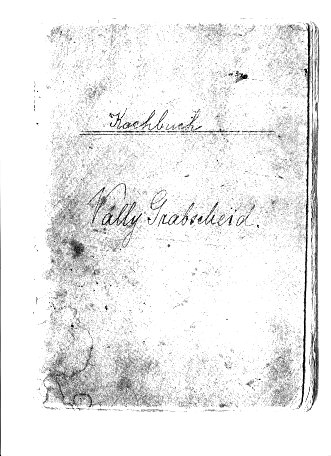

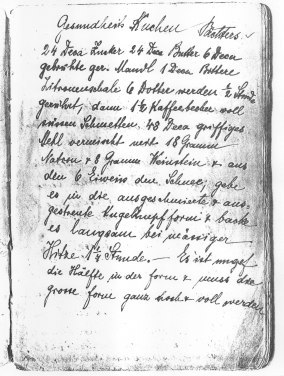

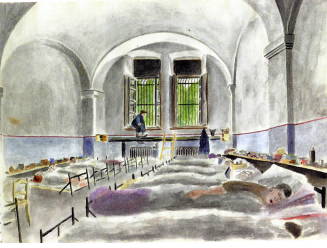

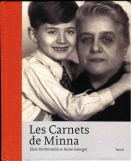

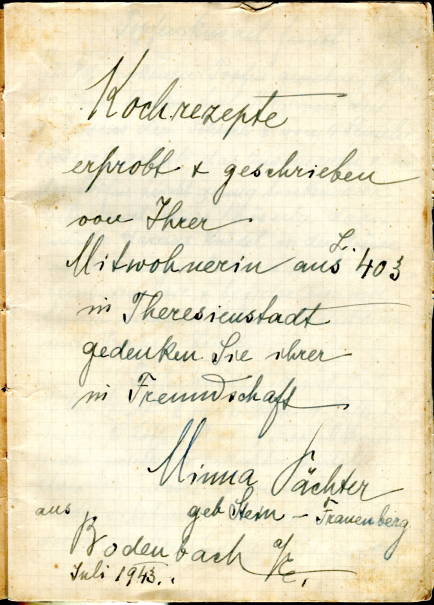

IntroductionThis is the story of a Czech family, rooted in a peaceful liberal environment not much different from today's US or Western Europe. Because it also was a Jewish family, its peace and security ended abruptly with the Nazi occupation of 1938-9. The story centers on my grandmother Minna. As a young woman she married Adolf Pächter [Paechter], a successful engineer whose factory made buttons from ivory-like tagua nuts. Adolf was a community leader, much older than Minna when they wed: as long as he lived, she led a happy, carefree existence, but after his death his wealth dissipated and she ended up having to support herself as an art dealer. When Nazi Germany overthrew the Czech republic, she was like most Czech Jews deported to the prison-camp of Terezin (Theresienstadt), where she fought hunger by compiling with her room-mates two books of recipes from the "good old days," as well as poems and more. Against all odds those writings survived the war and many years later, by strange routes, reached her family in the US. However, hunger sickened her (as it did to many inmates) and ultimately she died of it in the fall of 1944, just before most prisoners left in Terezin were given one-way rides to Auschwitz.

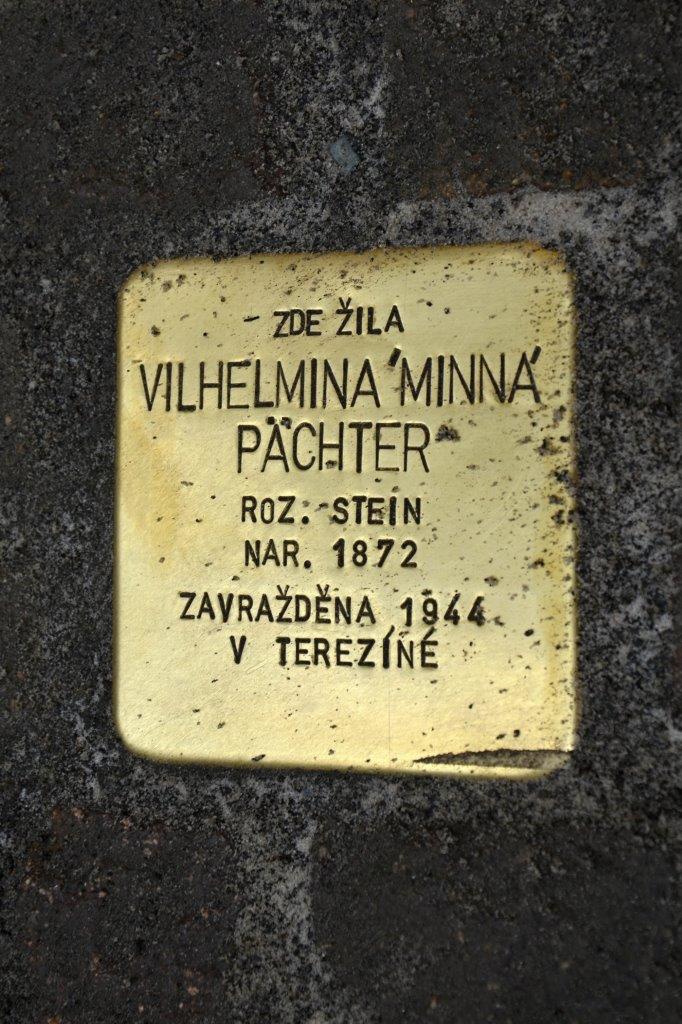

Minna's story is entwined with that of Liesl Laufer, the grand-niece who found her in the camp, took care of her and who, shortly after she died, was deported to Auschwitz. Thanks of her courage and luck, she escaped while being marched towards Germany on a snowy road, hiding until the Russian army arrived. Other parts of the story concern Minna's children-daughter Anny, who helped Jews escape the Nazis just before the exit gates slammed shut, and her son Chanoch (Heinz) who married in defiance of Minna and who settled in British Palestine. Some family members escaped to Britain, while others stayed too long and never returned. One reads these stories and wonders, "what would we have done in their place?" They were very much like us-educated, active members of a liberal society. Could victims of the Holocaust have resisted in some way and survived? The stories suggest that probably not: many were resourceful, but they were isolated inside an occupied nation . The Czech people, unlike others of Eastern Europe, were largely sympathetic to Jews, but they were a defeated society, subjugated without mercy by the Nazis. Most family members who survived were those who fled early, abandoning homes, possessions and careers. Through interviews and writings, Minna and those around her speak to us here. Here we also read about their lives before WW II, in the Austrian empire and in Czechoslovakia, years of freedom in a peaceful society. Even then life still had its ups and downs due to character and personal choices, as happens in most families. Minna's Early YearsMinna (Wilhelmina) Pächter was born in 1872, daughter of Heinrich Stein, a Jewish tanner in Hluboka (Frauenberg) in southern Bohemia, not far from Česke Budejovice (Budweiss) . Hluboka has the famous castle and mansion (now a museum) of the princes (Fürste) Von Schwartzenberg, and much of its life used to be linked with that noble family. Hluboka and all of Bohemia were at that time parts of the Austrian empire. Minna's son Heinz Pächter claimed that Heinrich Stein was a pleasant man, good-hearted and devoted to his family, and an enthusiastic flutist. At times he would close himself in his room and walk back and forth, playing his flute as he walked. His wife, Anna Stein, held the reins. Heinz'es stories suggest she was a hard person, maybe because that was the only way she could control her many children.

She grew up as one of eight daughters and at least one son. Heinz described her as "an honest woman… who loved reciting poetry and pathos, literature and any other kind of art. She had little talent for money… but on the other hand was a top-notch housekeeper. Meals, hospitality, cakes, coffee (most importantly coffee) were turned by her into a virtual ritual (but) accounting and trade were not among her strong points..." After finishing school Minna lived in Prague with her married sister Agnes Skal and graduated there from a seminary for elementary school teachers. At the same time (Heinz wrote) she secretly visited a famous former theater actress, Anna Wasing-Hauptmann, and learned from her acting and recitation--apparently well aware that her parents would never ever allow her to appear on stage. She had a nice resonant voice and a rich vocabulary, and it was clear that the stage attracted her. Later she lived for 3 years with an aunt in Budapest, in the Hungarian part of the Austrian empire, where she learned to speak Hungarian. At home she spoke German, the main language of Austria, but was also fluent in Czech, and spoke English quite well.

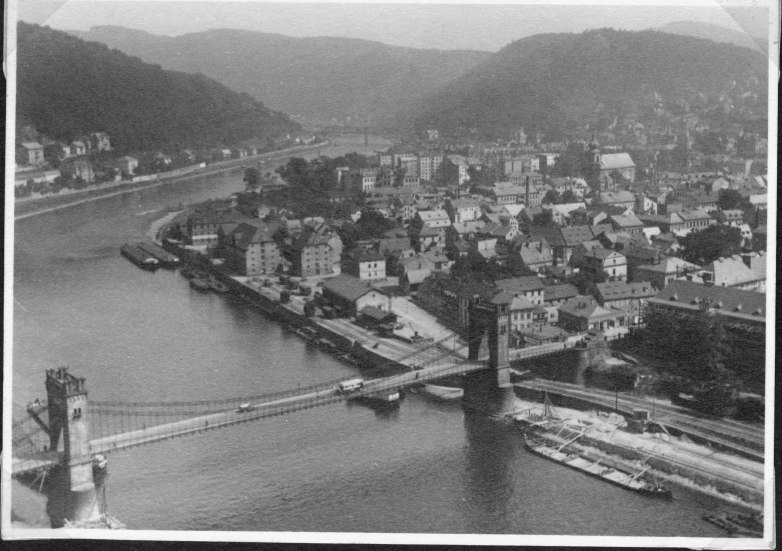

In 1900 she visited an older nephew, Leopold Kramer, a successful doctor in Prague. Dr. Kramer was a friend of Adolf Pächter, who had lost his second wife Adele two years earlier, and introduced Minna to him. Even though Adolf was older by 27 years, the two fell in love, and were married in Hluboka on 30 December 1900. In the pictures of the wedding, Adolf wears top hat and "frack" (formal tails jacket), Minna a white dress and a very serious face. Adolf PächterAdolf Pächter was the owner of a successful factory in Bodenbach (Podmokly nad-labem), located on the wide river Elbe (Labe), just before it flowed northward across the German border. Originally a village across the river from the castle and city of Tetschen (now Czech Děčín), by the time of Minna's wedding it had grown into a thriving industrial city of its own. Its prosperity can be credited to the 1851 railroad, following the river to Germany and the seaport of Hamburg, an easy way across the mountain chains that border Bohemia. Factories sprung up in the valley next to Bodenbach-and the town, at its northern edge, was recognized as an independent municipality in 1901 (it merged with Děčín in 1942). Adolf's son Heinz wrote:

"In Bodenbach almost every big business, every large German factory, had a branch. That is easily explained: German was still the local language, yet the place was outside the border, and factories in Bodenbach could supply the giant market of the Austro-Hungarian empire. Thus the town had (hand-written names uncertain) Guy Dralle (perfumes), famous chocolate factories (Joidan & Timans, Ruiges, Hauting & Vogel), "His Master's Voice", Odol, and more and more, a long list. In addition, there was local industry: Leonhardi (ink, pencils, office supplies), Daymon (batteries and electric torches), AEG (underwater and underground electric cables, and electric wiring)--and (also) a number of button factories. In my time the town had about 10,000 inhabitants (not counting suburbs), plus 12,000 in Tetschen… While Bodenbach was newer, livelier and more industrial, Tetschen was the seat of the duke of Thún-Hohenstein, with his famous palace from the 17th century, from which also came one of the heads of government of (Emperor) Franz-Joseph the First. Tetschen had superior schools, a gymnasium, a whole city quarter devoted to schools, the administration, courts of law etc., a large district hospital, public servants and a quieter, more comfortable life. There also existed near Tetschen the agricultural branch of the German university in Prague… In Bodenbach existed a Technion (Technikum, school for Engineers) which raised and educated a generation of young people [Many students were Jews], prevented from studying in their own countries by being Jewish, and that added to the Jewish life in the city. In fact Tetschen and Bodenbach were sister cities, a double city, joined in the late 1800s by a suspension bridge (replaced around 1925 by a steel arch).

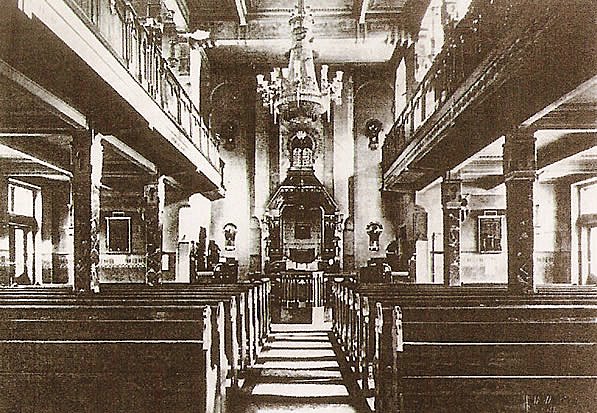

The area was also rather scenic, and the mountains on the north of Bodenbach (mostly in Germany) are known as the Saxon Switzerland. The city of Bodenbach, built along the road to Teplice, is sheltered beneath a forested steep mountain, ending on the river edge in a steep cliff, the "shepherds' wall." Adolf was born on 14 September 1846 in Wisonitz near Moravské Budejovice, studied engineering in Vienna, and opened a very successful factory for buttons in Jilove (Eulau) near Bodenbach-Podmokly. Many were made from "stone nuts," the very hard nuts of the Tagua tree of South America. Around 1880 he moved his factory to Podmokly . Heinz described him in these words: "My father was short, a bit of a fancy dresser, always clean shaven and cleanly dressed [but later he grew a handlebar mustache, the style of his times]. He loved to wear jewelry, rings, a pocket watch, chains etc. He was very popular among men, who always asked for his advice and help. And he was always busy, involved in public affairs and a tyrant in his family and factory. I know that when he was young, he used to work in businesses in Vienna, Karlsbad and Teplitz. He became a partner in a factory, received insurance money after his first wife died [Martha Hirschl], and founded a factory for buttons--first located near Bodenbach. Around 1876 or 1879 he bought a factory, part of which was already built at its present site and was standing vacant, at the end of Bodenbach." Adolf married 3 times. In 1873 he married Martha Hirschl with whom he had 4 children and who died in 1890. In 1892 he was married again, to Adele Hirsch who bore two children but died in 1897. Minna was his third wife. The Pächter FamilyWhen Minna arrived in Bodenbach, she had her hands full, in particular, taking care of Käthe, youngest child of Adele, a high-strung 6-year old. She was put in charge of the big household, in a house of 15 rooms, with 12-15 members sharing meals. "The organization of the household was strict--Adolf was merciless in this matter. Even the menu was rigidly set--in general the arrangement was that every Monday had the same lunch, and so on, Tuesday everyone knew that schnitzel with peas would be served, or on Friday a strudel and no meat…" Adolf was the president of the Bodenbach Jewish community, with a few hundred congregants. Religious services were held in a garden pavilion made available by Adolf, and Minna headed its organization of Jewish women. Heinz recalled seeing her at a Purim ball dressed up as the empress Maria Theresa, with a wide skirt and a wig of gray locks, a truly imperial figure. The care of the younger children was entrusted to a German nanny, while Minna was often busy elsewhere. She had a social circle of the "high" Jewish society, meeting once a week on a fixed day, for coffee and cake in one of the ladies' homes, and there were many other such involvements. Among her more serious concerns was the strict diet of Adolf, who suffered from diabetes; insulin was still undiscovered. She closely oversaw the cook, and sometimes cooked for him herself. But according to Heinz (who often clashed with her), up to 1915 she did not appear to have much time to spend with her children. "She was simply distant from us". Of course, some of those children were already young adults. Adolf insisted that the entire family eat dinner together. As Anny told (with some exaggeration), "…lunch, we ate with a Fräulein, with a governess, but dinner we had with him. And God forbid, (if) I would have not put my elbows [up] as they should be, or. .. got up from the table without saying "may I be excused?" I think he would put me in a room with water and bread." From the early 1900s she collected antique objects, in particular art. "That hobby later became a profession and livelihood, for which she even passed a test before the Reichenberg commercial bureau, administered by the manager of the [Reichenberg] museum. In general, her aesthetic sense, her knowledge of art, were "in her blood" and expressed itself by her great expertise in diverse arts--theatre, music, opera (especially Wagner's operas), drama and singing. She played the piano, but not well, and as her children became better at that, she stopped playing altogether. Among the writers she loved Schiller most of all…" "In the years after WW I a new star appeared in her sky: Martin Buber. She recited so frequently his best known book of those times, "Three Conversations about Judaism," that she knew the best among those conversations, the first, by heart." Adolf had six children by his previous marriages. Gisa (Giselle), Alfred, Rudi and Meta (abbrevation of Margarete but known as "Mimi") were children of Martha Hirschl, his first wife, while Emmy and Käthe were daughters of Adele Hirsch. Emmy and her daughter survived the war, as did Liesl, daughter of Käthe. Emmy was settled in London, but most of the rest of the family ended in the concentration camp of Terezin (aka Theresienstadt ghetto) and were sent by train to Auschwitz in the final transports of September-October 1944. Liesl alone escaped: before that, in Terezin, she found Minna and kept her alive in the ghetto hospital where she worked. Most of the information about that branch of the family comes from the translation of a memoir in Hebrew by Minna's son Heinz Pächter (renamed Chanoch Ben Aris in Israel). The Bodenbach SynagogueIn the early 1800s few Jews lived in Bodenbach , but that changed when Austria in 1848 granted freedom of religion to all citizens of its empire. Already in 1875 they would meet for prayer in apartments of members of the community. In the year 1885 a committee was formed to work towards the establishment of a synagogue, and Adolf Pächter made available as prayer hall a garden pavilion erected for this purpose, at his own expense, on his property at the factory. In 1870 the congregation founded a burial society, and in May 1894 it hired its first rabbi, Max Freund. Later Adolf got together with two other well-off members, Karl August Lingner who founded the Odol company, makers of Odol toothpaste and mouthwash (still sold in Germany) and a Mr. Duschak. Together they provided money for the construction of an ornate synagogue near the main street of Bodenbach, on the steep road to the top of the cliff overlooking the river, the "shepherds' wall" (Schäferwand, Pastýřska Stěna). It was a striking structure in "art-nouveau" style, with Moorish windows, a sanctuary seating about 200 and two domes on top. The glass industry provided opulent chandeliers of Bohemian glass.

Because of the steepness of the site, the synagogue had five different levels. They included offices, a kitchen, an apartment and a smaller meeting room which could be heated and which during the colder months could replace the sanctuary. Embedded in the wall is a foundation stone with the date of 10 March 1907 chiseled in. The congregation employed a rabbi-first one was Max Freund, then Oscar Karpeles, and the last Dr. Farkaš from Slovakia. The congregation also had a cantor; the last one was named Insel, he taught Hebrew and occupied the apartment. In addition the congregation had a caretaker (shamash) and a well-trained choir of members. The synagogue served well until the Nazi occupation at the end of September 1938. The Germans trashed the sanctuary, tore down the balcony and converted the building into storage and a youth club. Practically all Jews-including Minna and her family-fled Bodenbach, most of them moving to Prague, which half a year later the Nazis also occupied. Only one of them came back from the concentration camps-Elisabeth (Liesl) Kaplan, who survived Terezin and Auschwitz, fled a "death march" and reached the Russian army. Minna died in Terezin, and her parents, Liesl's husband Erich Reich, her sister Helena and most other relatives ended their lives in Auschwitz. Shortly after the end of WW II Liesl returned to Bodenbach together with Dr. Farkaš, both hanging onto the steps of an overcrowded train. Later Dr. Farkaš asked her to come to the synagogue, "There will be a service, I don't know when"

Here is what Liesl told (in 1984): " I came to the synagogue and I just couldn't believe my eyes. The women's section, which was upstairs, balcony, was all pulled down. The whole synagogue, the Germans used the synagogue for their horses. So the floor, which was of (?), was just broken out. The whole balcony didn't exist any more. The nice wooden benches weren't there, the whole aron kodesh [holy ark. Holding Torah scrolls] was broken out. But, there were a few very primitive chairs, and on these chairs was about a minyan (quorum of 10)… Jews from Carpatho-Russia, who fled to Bodenbach. And there was Dr. Farkaš as the rabbi again, and Löwy, the shamash again. And when I came in they told the congregation that I am really from Bodenbach and that my grandfather erected the synagogue. But I tell you, it was so horrible, it was one of the instances I just sort... well, what happened? It's unbelievable! Where are all the people? And everything gone. I went to the side room, and in this side room, which was in a much better shape than the synagogue, was a picture of our grandfather. I thought.. I couldn't believe it. But it was there. And I didn't take it down. I didn't take it with me, because I thought it was too heavy… It's been a colored photograph, they somehow colored the photograph, I think, at that time. But it's been, what my mother called the official painting of grandfather. That's been it." In 1942, under German occupation, the city's status changed, as it became part of its sister-city Děčín across the river. The neglect of the synagogue continued under the Communist government, which seized power in February 1948. Until the "velvet revolution" of November 1989, which restored democracy, the building was used for storage of official records. For a few more years it continued as a storehouse, but then the new government decided to restore it. On 14 June 1994 the building was returned to the local Jewish community and in 1996 it was declared as one of the cultural monuments of the Czech Republic. It currently serves both as synagogue for the congregation and as civic hall for public lectures and concerts. On 1 September 2007 it celebrated its 100th anniversary. A Torah scroll was restored to it on 2 May 2005 and is again read on Sabbaths and holidays.

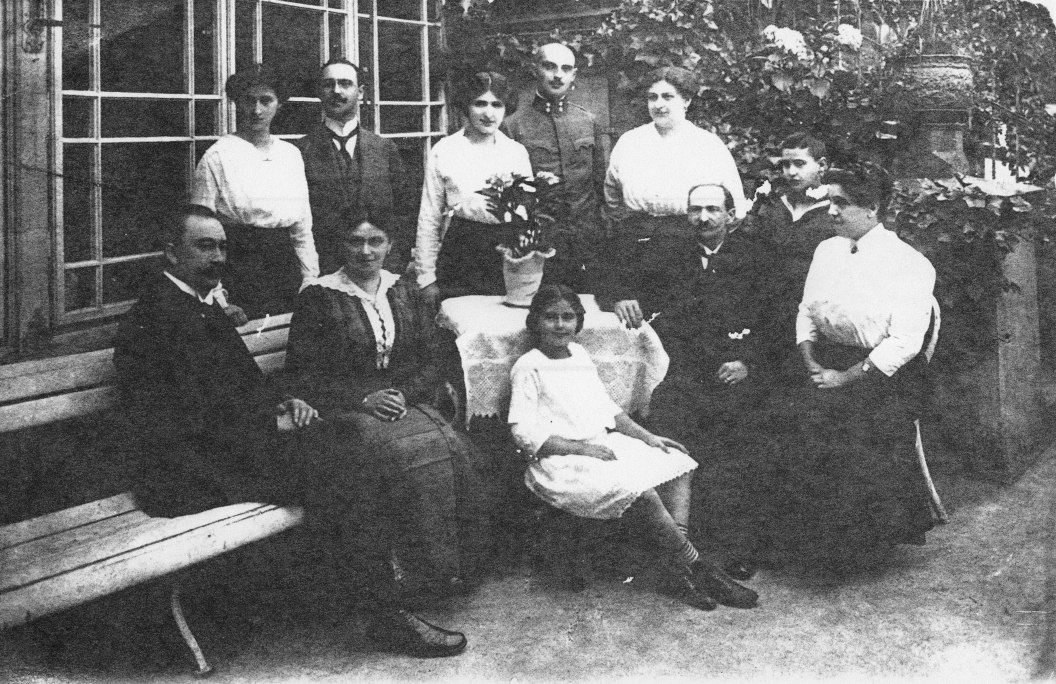

WW I to the Nazi OccupationWorld War I broke out at the end of August 1914, triggered by the assassination of Austria's crown prince. Germany joined Austria; ever since the days of chancellor Bismarck, it had cultivated a large and strong army, and it quickly became the dominant partner of the "Central Powers" alliance. The "war effort" required many workers of the factory, which itself was kept busy by the government. As it turned out, much of the work was paid by war bonds, which became worthless after the collapse of Germany and the Austrian empire. Minna enlisted in the "war effort." Bodenbach was a border town, an important railroad station between Germany and Austria of those days. Soldiers passed the station in a constant stream, day and night, and the city's upper-class ladies worked constantly and took turns distributing sandwiches, cakes, coffee and soup to traveling soldiers. She put in half a day's work 2-3 times a week, and later received a German medal for it. Proud of what she did, she kept the medal with her when she was taken to Terezin, and it saved her there from an early trip to the extermination camp. A photograph of the entire family exists, taken around 1915. Adolf in the center-large handlebar mustache, next to him Minna flanked by her children Anna and Heinz, and the other children all around her, with Rudolf Mosauer, husband of the eldest; Adolf's son Rudi is standing, in military uniform. Mimi also married, forced by Adolf to leave the man she wanted and marry one she did not. Her sister Emmy in 1913 fell in love with a young engineer, Hans Federer, whose brother Oskar was general manager of a large factory in Moravia (Wittkowitze Eisenwerke) of which Hans became chief engineer. Adolf also objected strongly to that match and wrote Hans nasty letters, but Emmy waited and ended marrying Hans in 1917, after Adolf had died.

When the Nazis invaded, Emmy's daughter Marianne was studying in London, but Hans and Emmy had waited too long. They escaped to London (the factory had secured their admission without a visa) after the Nazis occupied Prague, but could only take what they packed in two suitcases. During the war, Hans worked as an engineer for the British. Oskar had escaped earlier and managed to transfer enough property to England for a very comfortable living. By the time the war broke out Adolf was seriously ill with diabetes. He retreated to two huts on the mountainside behind the factory, and tried to manage his business by phone, delegating many duties to Rudi and Albert, who unfortunately lacked his talent and drive. Minna did not realize that among his visitors in the huts were lawyers, who changed his original will of 1910 or 1912. According to the old will, Minna would have received part of the factory, as would Adolf's 3 sons, and each daughter would receive a very substantial amount of money, in cash and in houses. The new will gave the factory to Alfred and Rudi, and other properties were divided-- Minna got one half of a big rental house in Teplice, and some other houses were also divided among the children. In 1922 she bought out the other shares of the Teplice house, improved it and sold it in 1926 to a Czech school. In his memoir Heinz wrote: "On Tuesday, 14 October 1915, my father died, and on Sunday 19 October the burial took place. Our town had never seen a funeral like this: schools, the municipality (my father was a member of the council), firemen, factory workers--a nearly endless procession went from the synagogue to the cemetery. Only then did I see my mother again, dressed in black, with a long veil, supported on the arm of my eldest brother… she cried when the grave was sealed, after eulogies… The situation was gloomy, and as my mother said, was like a house without roof." After Adolf's deathThe change in the will made Minna bitter, and for three years her lawyers fought in vain to overturn it. The prize proved to be less valuable than she believed. Alfred and Rudi were not successful managers of the factory, maybe because of increased competition, especially from Italy, and the factory declared bankruptcy in 1927. Like Adolf, Alfred also suffered from diabetes, and he died of it shortly after the Nazi occupation. The bankruptcy left him with little property, mainly a permission to continue dwelling in his rooms. All those years he had a relationship with a Christian woman, the accountant Miss Kostubačky, but he did not marry her because she was a Catholic: he would have been expelled from the house and disinherited if he did. Adolf was in many ways a tyrannical ruler of his family: he once slapped Alfred in the face after he forgot to renew the insurance of the house and factory. Miss Kostubačky stayed with him, even after he lost everything, and later, when the family was imprisoned in Terezin, was the only one who sent it packages of food. After the war Liesl looked for her in Bodenbach in order to thank her, but she had died of cancer a short time earlier. After Adolf's death Minna moved to a large apartment in Bodenbach, not far from the synagogue. Having earlier on studied art history, she saw she could support herself by trading in old art and jewelry. She applied for and received a permit to maintain a sales shop for antiquities in her apartment, citing her examinations by the museum superintendent in Reichenberg. Living in a border town, she had contacts and customers in both Austria and Germany. It was actually a good time to get into that line of business, because many holders of noble titles lost income and readily sold family heirlooms. Art was on display in the apartment, and buyers could inspect it there. Heinz wrote " The apartment became a virtual museum and any person who ever saw it--and there are many of those in the country (Israel)--will confirm her good taste. It was a dwelling, and at the same time, not an ordinary dwelling. Everything had a use, and yet almost everything was for sale. There was a yellow salon and a pink salon, but one bright day one of them was sold (or both?). She bought furniture from various places, sent it to be upholstered with fabrics of her choosing, and suddenly one day there appeared a green living room. Her goods included Rococo rooms, French and Viennese Empire style, Biedermeier (that is, 1815 to 1825). She had two giant armoires, one Flemish from 1662, one German Baroque 1675. There were some 10,000 etchings of all periods, in particular Dürer, the famed Callot, French, Czech and German, drawings and so forth. There were two paintings of Laucret (contemporary of Watteau), a special collection of drinking goblets of Karlsbad from the time of Goethe, and a collection of cut glass from different periods. Silver utensils were mainly from the Baroque, the Rococo and up to about 1835. However, there remained wide areas she refused to touch, and she clearly stated that she had no expertise on them, such as Gothic furniture, oriental objects of India, China, Java and Japan, or Roman and Greek antiquities. Any offers of such items she turned down, justifiably. There were also Gothic and Baroque wall hangings of the 15th and 16th century, and some collections covered special topics. I helped her greatly in assembling these collections and in their description, using the enormous professional library which she had available. (For instance: I collected for her the handwritings of famous persons, which she sold well. I located books, histories of wall hangings, and so forth). She also collected antique Persian rugs, fabric items, ancient needlework and so forth. She had a marvelous taste. One of her best-known pictures was by the Dutchman Meinderd Hobbema, a landscape with poplars and a muddy road, oil on wood. A great part of my time was devoted to helping her, to produce for her photographs and then assemble them into albums and pictures, which she sent abroad to buyers and to interested persons. Sometimes I worked simultaneously with 3 cameras, all taking 9 x 12 (centimeter) pictures on glass plates. I developed and copied everything by myself, and therefore this did not cost her much and allowed a good profit. For instance, I photographed dozens of miniatures, English, French and Viennese of all periods. But not to forget: the modern era, the era of machines started around 1830-1835, and her interest extended only up to that point. Modern art, for instance, did not exist for her at all. Sometimes she sent me (and later my sister) to various cities, with jewelry, pictures and so forth. But I did not like too much those trips." She was close to her daughter Anna, but her quarrel with her son Heinz grew more and more confrontational as the years went by. Heinz at early age became concerned with what he saw as spiritual aspects of life. He believed in astrology, also convinced himself he could divine the fate of a person from the wrinkles in his or her palm, and at one time became very concerned with his Jewish heritage. He asked that Sabbath candles be lit, a blessing be said over them and over wine, and that only kosher food be served to him. The household, however, was "liberal," and meals included pork. Minna brought from Prague tasty pork sausages and convinced Heinz that they were kosher. Later in his religious studies class he discovered this was a lie. As he later wrote "Something like this must be absolutely avoided, it destroys the trust a child feels towards his mother…" ZionismBy that time, most Jews in western Czechoslovakia were drifting away from religion. They were attracted instead to Zionism, aiming at a Jewish revival in the ancient homeland of Israel. That country, ruled by Turks in the years prior to World War I, afterwards became the "British Mandate" of Palestine, an interim state formed by the League of Nations under the stewardship of Great Britain.The active Jewish community of Bodenbach included a Zionist youth club "Tchelet-Lavan" or in German "Blau-Weiss", after the colors of the Jewish prayer garment. Theodor Herzl later proposed these colors for the flag of his Zionist movement, and they became the flag colors of Israel. Minna was skeptical. But she did not object when her daughter-6 years old or so-- was brought to the club by an older girl. As Anny later described it, "… in my family nobody knew anything about Zionism... it was not, it was not chic, it wasn't fashionable, Zionists were poor people in Russia, in Poland, but not the well-to-do upper middle class, they were no Zionists" "…we came once a week together and our leader told us about the aims and about how and what and .. it was so far out. At this time, when I was a little girl, it was far out. Then the Zionist movement became much stronger, and then .. I think when I was 13 and 14, then already was quite a movement…" -- "Did you read books about Palestine?" Yes, but there were not too many books about Palestine. There were some very good speakers who came. And then came a young man by the name of Yakov Meller who was a student. He made evenings where he spoke with great warmth and with great presence about Jews who came from Russia and Poland, of which we, living in this very secure and well-to-do Central Europe, didn't know anything. --"What did your father say? "He said everybody has his crazy ideas. "Leave her, it's good she doesn't want a horse, a racing horse." (laughs) "Leave her." So I was the only one, nobody else. It was a small club, only 7 members. -- "What did Heinz… do when he was young?" "He was very good in music, he was quite good in writing, he was very good looking. .. and then he decided he wants to study, not in Prague, but he wants to go to Germany to study. He wanted to study--now you say 'political science.' … He studied at Frankfurt, made his doctor's degree in Frankfurt, and afterwards stayed one year longer at the university to make another degree, which is called "Diplom Kauffman." Heinz in his memoir explained his choice of university: "In October of 1923 I went to Frankfurt. Only now do I realize why I chose that city: it was the most distant one from Bodenbach."

Most of the information about that part of her life comes from the memoir of her son Heinz and from interviews of his sister Anny Stern. Because the latter is not always consistent (e.g. her claim that Adolf died of pneumonia), here Heinz'es memoir is the main source, though not the only one. He wrote, among other things: "Her stand towards Palestine ("the Land of Israel") was anti-Zionist. She opposed my joining of "Blue-White," a Zionist youth movement. But she did not stop me from doing so, in 1919. In the summer of 1920 I was an apprentice to a locksmith in a big house, and also in the summer of 1921, each time for one month [I still have documents about those times], because I had intended to learn metalworking and emigrate to the land (of Israel). Fate decreed that would not happen, but in any case I started on it. In 1935, when I announced to her that I intended to emigrate, she wrote me "I did not send you to the university and did not let you acquire the doctorate so that you would go to Palestine and become a worker!" She had no feeling for Zionism except as a general sentiment. As soon as it was legally possible, we went to the courthouse where I was declared an "adult", at the age of 19 rather than 21, and so was given access to my bank accounts, which were frozen by law until I reached 21. I transferred to her all my inheritance, with a detailed and agreed-upon stipulation, that from this money she would send me a monthly stipend, allowing me to live at the university and study. This money was to be absolutely sufficient for 5 years of studies (unfortunately, she later did not keep her word). In 1923 I passed my matriculation tests and as my reward I received from her a trip to Italy. I enjoyed it very much seeing the great world for the first time (earlier I had been with her in Vienna and Budapest, at her sisters). … I found a rental room with a widow and lived there. She (my mother) had a phone, and in the evenings she called me up, phoned to me, and woe to me if I wasn't home. Some evenings I wanted to go out and could not, because I waited for her call, but she never ever came to visit me. Sometimes she would not write for weeks, at other times twice a week. After March 1924 my mind no longer cared for those things... Meanwhile the German Mark stabilized and business suddenly got bad. The value of the money came back (and Czech currency no longer enjoyed a privileged status). And the money she was supposed to send me did not arrive. Imagine how a student feels without a penny in his pocket, who has turned his money over (to his mother) and it did not arrive. To work "on the side" was not allowed at that time (today, in America, that is possible, but then not at all, because I was a foreign citizen!!). When I came home on vacation I saw debts on one hand and waste on the other, excessive hospitality, lack of planning and no keeping of accounts, and I simply seethed, blew up. But I could not change a thing, and in addition Anny sided with her, Anny who received a much preferential treatment with her. Why, I do not know…Our relations were not warm. Never can I recall an open-hearted conversation between us, kind, human. And still she had an enormous influence on me, until I got to know Käthe. His sister Anny ("A") in her interview, told her own view of Heinz'es studies and of Käthe: --"And Heinz studied where?" A. "In Frankfurt. Frankfurt am Main, he studied at Frankfurt, made his doctor's degree in Frankfurt, and afterwards stayed one year longer at the university to make another degree, which is called "Diplom Kauffman" (certified trader) I don't know if this exists .. here. He studied under an extremely well-known ecconomist, Sommbart, who was really a great man. Sommbart and Oppenheimer. --"Was your father still alive? A. No! … My father died .. of a pneumonia. Would there have been penicillin, he would have lived. That's why we live so much longer now. --"Did Heinz write to you from the university?" A. Yes. He wrote, and I was there with him, for a year. --"What did your mother think about his study?" A. I don't know any more. Believe me .. I don't think .. it was just a matter of fact, he went to study, and he had to do good, and that's it. And then, before he went he had the possibility to study in Prague and he had the recommendation of Dr. Englisch, who was then the minister of commerce for Czechoslovakia, who was a friend of my mother. And Englisch said, "I want to keep an eye on the young man when he's finished with his studies." And when he wrote his doctor thesis, and then as a Diplom Kauffman, Dr. Englisch offered him a job in the government, under him. In the ministery of commerce. But he didn't want to go to Prague. He wanted to stay in Germany, he wanted to stay in Frankfurt, he had then already liaison with Käthe, Käthe Dore, and to the horror of my mother, married her.

--"Who was Käthe Dore? A. Käthe Dore was quite a person. Her father was a Prussian Junker, was Intendant of the Schauspiel Haus [theater] in Breslau. His name was Freiherr von Schipfer. He married an Anna Franck, I believe Anna was her name, Jewish, and the brother-in-law, the brother of his wife, was Professor Fritz (James?)Franck, I think you know who he was, he got the Nobel prize in nineteen hundred .. in chemistry, 26-30, it must have been before... [1925, in physics, with Gustav Hertz for expt. on atomic energy levels?] "Onkel Fritz." And "Onkel Fritz" was "ausgebürgert" [stripped of citizenship] by Hitler, with Thomas Mann. And he stayed with us for, I believe, a week, in Bodenbach. I must say I didn't feel very comfortable with him, because I was afraid. If you remember, Theodor Lessing was a very well-known journalist, who wrote against the Third Reich. He was in Marienbad, which was a very well-known spa, where the Prince of Wales always went. He was shot while sitting in his room, reading a book. From a promenade outside. And I was jittery (?) when this Onkel Fritz stayed with us, because he was .. he got, had the Nobel prize, he was deprived of his citizenship, and many people came to see him in our house. Was a very nice man with a white little goatee, very bright eyes... (all this from Anny Stern; I have no proof for this identification. None of Dr. Franck's photos shows a goatee, no one by that name among chemistry laureates. )

--" How did they get together?" A. How they met? No idea. She lived in Frankfurt… Dorothea's mother, Franck, came from a very well-to-do German bankers' family, and the name of the bank was Speier, Ellison und Co. You know, there were many Jewish banks, like Bleichröder, and Rothschild, and there was one Speier Ellison und Co., and from this family the Francks came. --" And what happened then? Where did they get married? A. They got married in Frankfurt. --" Did your mother go there? A. No. She didn't even know. He married .. I don't know how it was, I know she was very unhappy. Very unhappy. And then they came to Bodenbach, and you know, it all is like a blur. When Heinz came and said, what should I do now, I said something, I should never open my mouth so quickly. I said, "How can you ask 'what should I do.' Where can a Jew go now, in these days, if he is going. There is only one place to go and this is Palästina." And he really went to Palestine. And I think he should have gone to England, it would have been better for him. --" What did you think of Dorothea? How did she treat you? A. She knew me when I came as a student to Frankfurt. She was very nice and very sweet to me, but the whole of Bodenbach was horrified and said, "my God, he married his own mother." Because she looked .. she looked very old". She was actually eight years older then Heinz, born in 1896. Her full name was Katherina (Käthe) Dorothea Naria Louise Schipfer von Sausal. (Sausal is a small region in southern Austria, close to Hungary). (Later George Stern ("G") joined the taped conversation, mostly in German, which is translated here) G. Dorothea was actually tremendously superior to Heinz, spiritually. A. Yes! Much smarter. G. And she was, how can I say it… Heinz was by nature very lazy. A. Terribly lazy. G. And she had really… they assembled a giant library, from Germany. She was well-read, she was very smart. A. Very educated. G. She was homely, and she was a good wife. And I think that the death of Dorothea (1941) did tremendously…how can I say it, it did not depress Heinz, but touched him tremendously.

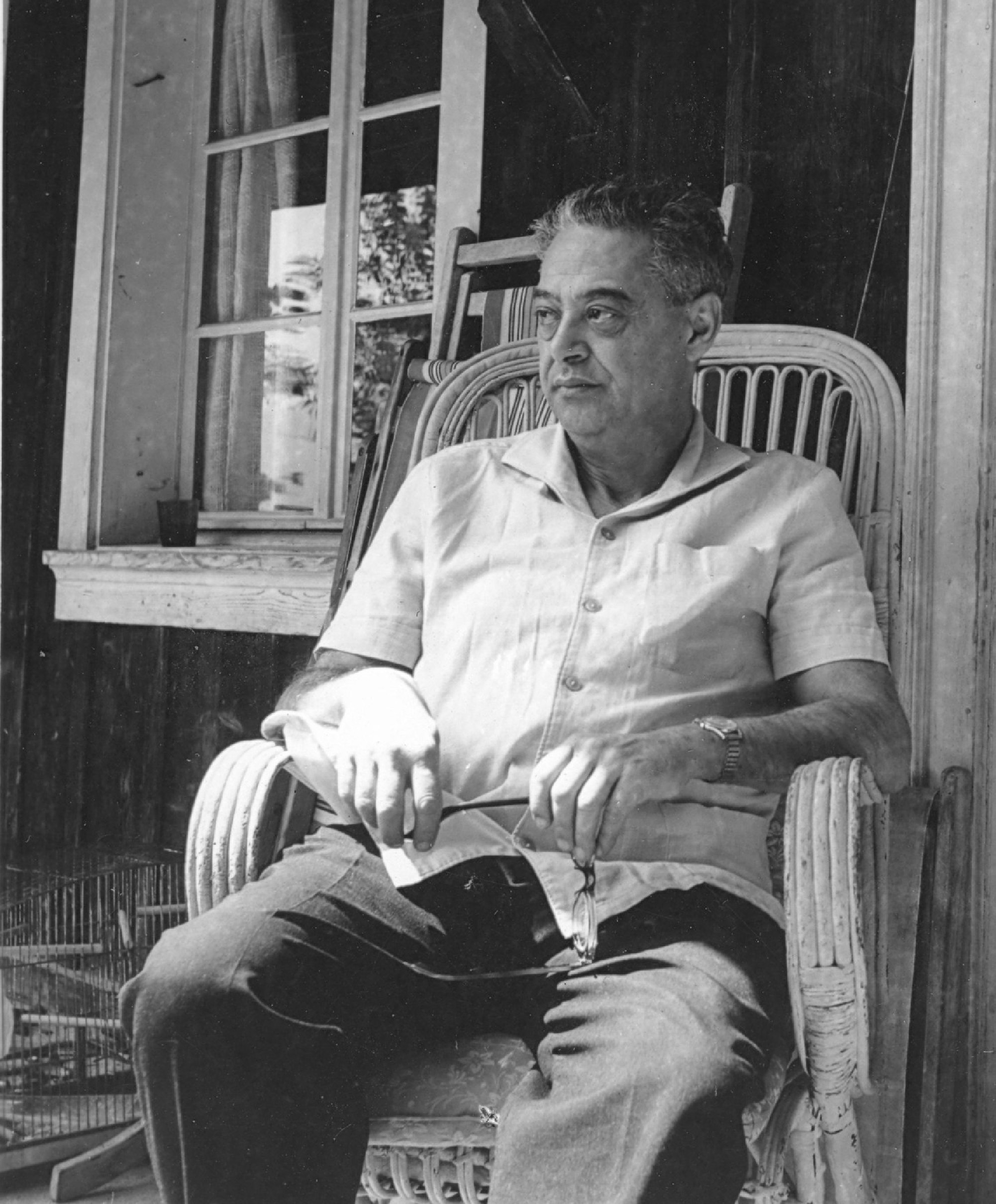

--I thought he was with the electric company. A. No, that was later G. Tell me, what was that called, didn't he have a farm in .. Migdal. A.: He had bought it. G, And that was what the Arabs destroyed and took over. And then he moved to Tiberias, and he worked for a time in Tiberias as a teacher (A.: and with the electric company), and actually Dorothea helped him tremendously with that, I have to say. She was very dedicated, and Heinz used to play there the violin, and play in a quartet, he didn't have much. The business of Blue Band was actually brought over there, they had overall nothing ("auf kappores") there. But he had a stock, and from that stock he distributed to the different groceries. And the grocers would come, whenever they needed anything, he took out and got paid. A. (laughs) As I can recall, it was like a scene from Arabian Nights. It was all so primitive, who ever knew of air conditioning? The heat was enough to kill you [Tiberias is 200 meters below sea level] . In Germany Dorothea and Heinz in 1933 had a boy, Frank Peter Gabriel As a child he was mostly addressed as "Pitty", but in Israel, in later life, he favored Gabriel ("Gabi") and went by his Hebrew name Chanoch (soft ch). Like the rest of his family he adopted there the surname "Ben Aris." "Aris" in Hebrew means tenant farmer, one who works the land but does not own it, same as Pächter in German. "Ben" means "son of". Over the years Heinz had many interests, some of them rather unusual. Both he and Dorothea shared an interest in genealogy, and most of the detailed family information cited here for the Pächter side was collected by them. Heinz also delved into chiromancy, reading the future by the creases of the human palm and the shape of the hand. He collected handprints of people, and wrote in manuscript a book about chiromancy, never published. Later in life he gave (unpaid) palm readings. He was also interested in astrology. In Tiberias they rented an apartment in the "house of Ben Israel", an old rundown house across the street from the Schweitzer hospital, in the upper (Jewish) part of Tiberias; 100 meter above the lake, it was marginally cooler. They shared it with another family, although the house most probably started as a single-family dwelling. It had two rooms--a living room which one entered through an arbor-shaded balcony and which held Heinz'es piano, and a side room with wall storage. The kitchen was cramped, and beyond it was a balcony used for laundry and storage, with a raw concrete washroom/toilet on the side. Grown-ups slept in the living room, where at night a storage tub with bedding was pulled out from under the day-bed; their son (and in 1942, also David, son of Anny) slept in the other room, with a massive front wall two feet thick, leaving enough space between its inner and outer windows for a child to sit in. As noted, Dorothea developed cancer and died 24 August 1941, forcing Heinz to take care of a young child as well. His sister Anny could hardly help, she and husband George lived in a large wooden container-crate in which windows and a door were cut, next to a small restaurant she and George Stern operated outside a large army camp in the south. Through friends Heinz actually found a young wife, Pninah (Pearl) Schlafer, who promptly took care of Pitty and also (for a year) of Anny's son David.

Pninah was born in the Ukraine in 1917 or 1918, at the height of the Russian revolution. The Ukraine at that time saw extensive attacks on Jews by irregular Ukrainian troops, and the family fled across the border to Kishinev in Romania, with baby Pninah carried by her sister Rivkah across the frozen Dniester river which formed the border. In Romania the family eked out a meager living, while the father, urged by his wife, applied for entry to the US. However, just when all the papers were in hand, the US closed its borders to immigrants, and the family went instead to Palestine (her father's choice), arriving in 1924. At first, the father operated a flour mill in Safed in the upper Galilee, but he moved to Haifa in 1926, ahead of the 1929 uprising by Arab townspeople in which twenty Jews were killed. For some years the family lived in relative poverty, but still Pninah managed to attend a teachers' seminary and then work as a teacher. She was a youthful, hard-working woman with strong common sense, a good mother to Pitty and later also to Itamar and Chamutal. But culturally she came from the Russian Zionist worker tradition of the land around Tiberias and Haifa, far from the German urban culture of Heinz and very different from his and Dorothea's. The Sterns of LovosiceOn 5 December 1930 Anny Stern married George Stern, a young attorney starting his practice in Bodenbach. The two had been friends for years, playing tennis together and skiing in the winter. George was born January 1899 in Lobositz (Lovosice, in Czech, the name used here) and so was 8 years older than Anny.

Lovosice is located on the same side of the Elbe as Bodenbach, about 35 miles upstream, and had at the time about 5000 inhabitants, including some 50 Jews. George's father Josef worked with his brothers in a grain mill, owned by their father Heinrich. In 1910 he built a large house across the church in Lovosice, where he and a brother lived upstairs while the street level housed several stores (and still does). The Sterns also traded in local barley, used England and Scotland for making whisky and shipped by river-barge to Hamburg on the North Sea. George was the second of 5 sons (with Oswald. Paul, Franz and Albert) and attended high school in the larger town Leitmeritz (Czech: Litoměřice) across the river. In 1910 Mr. Werfel, a prosperous margarine manufacturer, came by to show off his new motor car (a great novelty then) and invited the Stern boys for a ride to the garrison fortress of Theresienstadt (Czech: Terezin, name used here) about 4 miles away. This was a generation before Terezin became the country's main Nazi concentration camp for Jews. George was in high school when World War I broke out, and was conscripted by the Austrian army before finishing his studies. He served in Terezin, close enough to allow him to continue his classes in school. After the war he enrolled at the Charles University in Prague (founded 1348) and graduated there in law. He spent the next few years as apprentice-lawyer (Konzipient) in Tabor, Teplice, Benzen (Benešov nad ploučnici) and in Bodenbach, where he became friendly with Anny.

After the wedding the two settled into a beautiful apartment formerly owned by Adolf Pächter, and in December 1931 they had a son, named Peter Adolf (after his grandfather; later known as David). Minna had another large apartment, but she did not want to live alone, so in the end Anny and George gave up their separate apartment and moved in with her. The Nazi OccupationMeanwhile, across the border, the Nazi party took hold, aiming to expand Germany's power and Germany's borders, and bitterly persecuting Jews. Jewish refugees started arriving across the border, and they included novelist Thomas Mann and his daughter Erika; she was officially awarded a "domicile" in Czech Bodenbach. The border was open and people still rode the "theatre train" to nearby Dresden. George went there one night to listen to a speech by Adolf Hitler, who shouted at his audience. It left him shaken.In contrast with the growing separation between Minna and her son, Minna's daughter Anny grew increasingly close to her mother. The two were similar in attitude and temperament, and after a while Anny, husband George and son Peter (later David) moved to share Minna's apartment. George had a successful law office in town, but meanwhile across the border the Nazi party took hold, aiming to expand Germany's power and Germany's borders, and bitterly persecuting Jews. Some refugees stayed briefly in Minna's apartment. Once when George visited Dresden, a director of a department store, whose daughters were already in Bodenbach, gave him 80,000 marks, which he hid in an empty beer bottle, placed next to him on the train seat. Border control at the time alternated-one night it fell to Germans, next night to Czechs-and George selected a night when Czechs were in charge. Once over the border, he took the money out and had the Czechs register it in the name of the businessman. Most residents of Bodenbach were German, and spoke German. The Nazi party had a strong following, and Hitler's annexation of Austria in March of 1938 was followed by strong agitation to detach the "Sudetenland," the Czech border region, and turn it over to Germany. Czechoslovakia resisted, calling up its army reservists (George among them, a sergeant in the mountain artillery) and relying on support by England and France to block Hitlers overwhelming air power. He, however, threatened war, invited the prime ministers of the two countries to a conference in Berchtesgaden near Munich, and after some negotiations, forced them to agree to a German take-over of the borderlands.

Most of the stories here concern survivors, but the majority of Czech Jews did not survive the war. Almost all of them were sent to the Terezin (Theresienstadt) concentration camp, and many died later in the gas chambers of Auschwitz and Treblinka. Adolf's childrenOf Adolf's six children by his first two wives, only one survived World War 2-Emmy, daughter of Adele Hirschl. Liesl in her interview, said "All the sons and daughters of our grandfather were tall, good looking, but all of them, tall, good looking persons. I remember being asked here, some thirty years ago, if I am the granddaughter of Paechter, who had exceptionally good-looking and pretty daughters. They were tall. All of them. Emmy, she was as big as I am, and she was the smallest. They were tall, they were really good-looking, they had good manners, they were brought up with a good education, and all of them were a success. Because Alfred and Rudi weren't a big success-Heinz (too), you remember. And Heinz had the tools to be a big success, and he didn't do it, because he was lazy. I remember your mother telling me, I don't know how many times, that she found him a job, and he didn't want to take it. Her brother Heinz wrote about her: " To this day Emmy is beautiful.... She finished school in Bodenbach, and then studied in Prague in a school of "fine ladies," learning home economics and cooking, living with my mother's sister [across from the school]. There she met a young engineer, who had just recovered from a lung disease. She fell in love with him and when she returned home from her studies, around 1913, the young engineer, Hans Federer, came and asked permission to marry her. My father simply blew up. Years later I read copies of his letters: full of curses and threats, he should never again try to see her again, a man who has no substance, who will never achieve anything of worth, a sickly and weak man--I will never ever give you my daughter's hand… Approximately such words. But Emmy wasn't like her sister. She stayed silent. She might have been delicate and a refined, but she also had a strong will, and she waited. My father died in 1915. In 1917 Emmy married the man, in the middle of the war. My mother forbade me to attend the wedding, but in spite of this I went to the synagogue at the time of the wedding and I was close to tears. I also received a kiss from her.

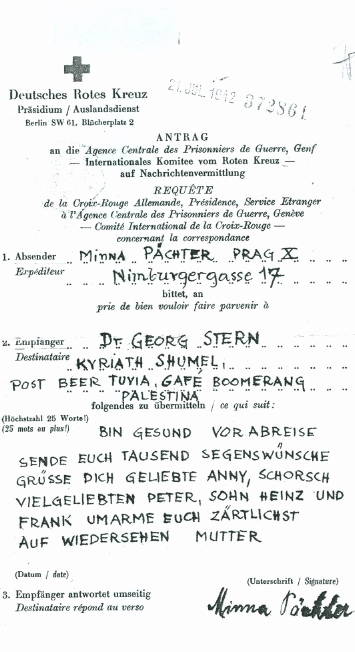

Her husband became later the chief engineer of one of the greatest factories in Czechoslovakia, second after Škoda, Wittkowitze Eisenwerke (Iron works of Wittkowitz) in Mährisch-Ostrau (Moravska Ostrava), a great conglomerate of iron, coal, mines and factories. His brother Oskar became general manager, very rich. They had one daughter, Marianne… who was studying in a college in England when Hitler arrived. Already in 1937 and early 1938 [Hans'es] brother transferred his money out of the country. He [acquired with it] …orchards, plots and houses in [Palestine] and abroad, in England, Canada and the USA. He transferred his money by sending to London (with official Czech permission) his collection of paintings, among them many by Van Gogh. There an "artist" created fake copies of the paintings, and Oskar Federer sent the copies back to Czechoslovakia. The originals stayed in London and were sold there (that, anyway, was the story being told). He lives today in Canada with his family, and remains rich. Hans Federer, his brother and (Emmy's husband) had a less happy fate. He and my sister [Emmy} were allowed to fly to London with two suitcases--in return for a hefty payment--after the German army had already entered Czechoslovakia, in the fall of 1938… Hans continued working as an engineer throughout the war, and even now is still working. My sister Emmy is a seamstress--and they managed to get … British citizenship and an old-age pension." After Liesl escaped the Germans, she worked as nurse, and met Dr. Fischer-Ascher, an eye surgeon, who was asked by Emmy in London to help find her family members. When Liesl responded, Emmy thought that the entire Pollak family was saved, and she was deeply disturbed when she later found that Liesl was the sole survivor. Emmy's daughter Marianne studied in London and married Gordon Bremner, who died in 1988. I visited her two months later, and have notes of that visit. From Liesl's recollections: "Adolf's son Rudi went first from Bodenbach to Vienna … but he got a heart attack, a very bad one. After that he was incapacitated…. Could have been '32-33. When the Germans occupied Vienna, they went to Brünn [Brno] and they lived in Brünn till they... his wife [Martha] and … one daughter Edith… born about 1925. Now, Rudi was in Brünn and he didn't have any job or anything to do, so I remember my aunt Emmy helped him and he got an agency to sell coals and that's been his job. In the end, Rudi was the first one to be deported. It's been in the winter, 1941-2, because the first transports were from Brünn and they were one of the first ones to go away. We got some two cards from him from a little place called Zamosc in Poland, it's near Lublin, where all the Jews went, and we knew when the cards arrived that we had to send them some foodstuffs, which we did [Liesl was still in Prague]. But it wasn't much and we were very anxious for it to arrive. It was some soup powder and some pulses [legumes], I don't know what. Things which keep. But after these two cards, we never heard of him or his family again. He was the first one to perish. Now … no, he was not the first one. The first one was Alfred. Alfred … went to Karlsbad. It was at the time the Sudetenland was occupied, that's autumn '38. He went to Karlsbad for one reason: to live with his sister Gisa [Gisella]. Gisa was in Karlsbad… at the time I talk about, in '38, she didn't have anybody there. Her husband (Rudolf Mosauer) had died and her two daughters weren't there. So Alfred lived with her, but the Germans interned them. Once more, as your mother [Anny Stern] told you, it wasn't a concentration camp, it was some open tent where they had to live and your mother somehow managed afterwards to get him to Prague. But he didn't live in Prague, he lived with his second sister, with Mimi Bunzel in Podjebrady. Podjebrady was a small spa about 150 kilometer from Prague. And they lived there together, Mimi [Meta, short for Margareta] … she was married to Leopold Bunzel from Gablonz, they didn't have any children and they lived in Podjebrady. But in Podjebrady wasn't any Jewish hospital and Jews… Alfred was sick for years already with diabetes and I remember that somehow we got news--I don't know how--that Alfred is in hospital in Prague, in a Jewish hospital. So of course, we went to see him there and he was there for some six weeks, and he died, but he died from diabetes." "What sort of person? Look, he was a very nice person, I remember him as a very good-hearted, nice person. But he was--his character was very weak. He wasn't the driving force your grandfather was, just on the contrary. And I think that it's been due to our grandfather, because grandfather was a man who wanted to govern, and he didn't leave Alfred or Rudi to do the work. Because Alfred was a very kind person but he had a weak character. That's all there is to it. And he was a bachelor and he never had a family and he was lonesome" Alfred lived with an unmarried woman, whom Heinz remembered as Miss Kostubačky: "She was the only one who sent my family packages of food to Theresienstadt, saving Lisel at the very least from hunger. But when Liesl, as a Czech officer, came in 1945 to Bodenbach to thank her, it was exactly on the day when the Sudeten Germans were expelled from Ulpendorf (the quarter where she lived) near Bodenbach, and the day she was buried, because a day before she died of cancer… Alfred never dared to marry her, because she was after all a Christian, and of course if he dared to do so, my father would expel him from the house. So she took care of him even after Alfred lost everything, and remained with no property, alone, poor, isolated…" Gisa and Mimi were later sent to Terezin and from there to Auschwitz. When the Nazis came, however, Gisa's daughter Martha escaped to England with her husband Hans Eckstein. Minna and Anny rented an apartment in the Vinohrady quarter of Prague, while Anny's son Peter was sent to live with George's relative Arthur Pešek, overseer of a farm in Vrchotovy Janovice, about 40 miles southeast of Prague. It was in a Czech-speaking area, and Peter, who only spoke German, was put in second grade of a school with an altogether different language, which, however, he quickly learned. Arthur was the husband of George's cousin Beda (Bedrička), daughter of Ottilie's sister Hedwig ("Heda"). He and his two sons were later killed by the Nazis, but Beda survived, and in the prison camp she adopted an orphan boy named Pavel (Paul). His son, also named Pavel, became an agricultural engineer in Česky Krumlov and (after the fall of Communism) a delegate to the Czech national assembly. In March 1939 the Nazis occupied the remaining Czech lands and turned them into a German "Protektorat," while Slovakia became a self-governing ally of Germany, and Hungary and Poland also annexed parts of the Czech borderland. The Czech army was dissolved and George Stern returned to his family, but not for long. Because he was a Jew he next received an order from the German government to report to a labor camp. He still had his Czech passport and a visa to Italy, so Anny advised him to go by train to Trieste, from where ships were still sailing to Palestine. The British government of Palestine only allowed 1500 Jews per month to enter, a tiny fraction of the number seeking shelter there, but Anny managed to send him money to live in Trieste. "Whoever left for [Palestine], whoever could go over the border and went to Trieste, brought George whatever was possible - money, or - I remember I sent him toothpaste and stockings and things -people had to take for themselves, they wouldn't take big things! And I spoke to the Palestine Office in Italy, and we always left a message for George, but that was all. And then when the war started I was very happy to be informed that they thought the only thing to repay me for what I am doing is to send George with the last boat before the war to Palestine, which he did." While in Trieste, he worked for a shop making ice-cream and cakes. He told about his work in a letter and also about watching Jews escape Europe on a ship bound for China: "The Conto Rosso was sold out to the last place, we were in the departure hall and I can only tell you, one must thank God, to be spared such a fate."

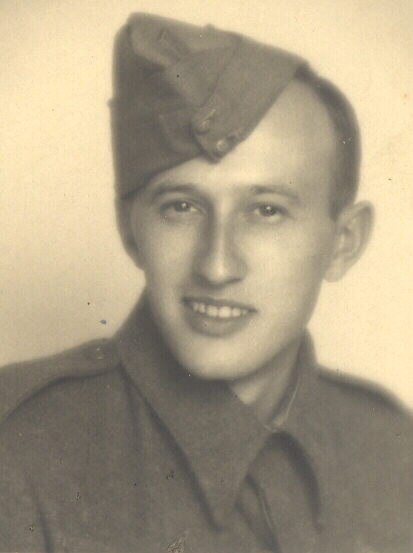

Frank VernonOne cousin of George who did escape was Franz ("Franta") Vohryzek, son of Emilia and Moritz Vohryzek, ("Aunt Milka"), another sister of Ottilie; in later years, in Canada, his name was Frank Vernon. He entered the law profession in 1930 and was the athletic member of the family, an expert in fencing and member of the Czech delegation to the 1936 Berlin Olympics. He remembered how Hitler visited the delegation and shook hands with all its members "though he did no seem to care much about us." After the Munich pact Frank escaped to France, and when WW-II broke out he joined a Czech unit in the French army. It was trained and sent to the front, but then France collapsed, French army units next to them pulled back, and the Czechs too had to retreat. Just as they arrived at the Seine the French blew up the bridge in front of them. The Czechs then noted some big boats on the opposite bank, and Frank and some others jumped in, swam over and brought them over to the other bank; when he came back he found that his uniform had been stolen. Somehow they all crossed the river and reorganized, but the German advance continued, and in the end he boarded a British ship for Gibraltar. From there he went to England, where he again joined a Czech infantry unit. Frank liked to say that during the war, he met the four leaders of the war in Europe. Waiting to be deployed, he organized a fencing group, and in that capacity he met with Churchill, and later De Gaulle. Because the Czech army knew about his legal training, he was appointed military prosecutor. Then it was learned that the Czech army in Russia, under General Svoboda, also needed a prosecutor, so Frank was reassigned to the job and sent to Russia with a Murmansk convoy. Luckily the weather was quite bad, keeping away the German airplanes and ships which had made the route hazardous, and they reached Murmansk on December 31, 1943. The admiral commanding the convoy was then invited to Moscow to be decorated by Stalin. An aide-de-camp was supposed to go along and Frank was asked to take the role, since the admiral assumed that, being a Czech, he understood Russian. Frank didn't, but was glad to get aboard the train. The trip took three days. Soon after leaving the admiral asked Frank to fetch some tea, so he went to a Russian and said "Tchai" which means "tea" in Czech: the word has the same meaning in Russian, he got his tea and his reputation as Russian speaker was confirmed. In Moscow the two were ushered before Stalin, who to his surprise was a small man, slightly built. Stalin spoke Russian, but it made no difference whether Frank understood or not, because Stalin's voice was rather faint (I guess a translator was present anyway). He then accompanied the Czech units as army prosecutor in their advance towards Czechoslovakia. Of his work he only said that at Dukla pass in Slovakia the Czechs were sent with inadequate support against entrenched Germans and suffered many losses. Some commanders refused to attack again and the Russians ordered him to prosecute them, but he knew they were good men and managed to evade the order. Somewhere along the way he met his wife Bella, who was born in Russia but grew up in Romania and who was serving with some Romanian army units. When the Russians arrived she was told that the Russians were conscripting all Romanian girls and the advisable thing to do was to forestall them and volunteer to the Czech army. This she did, there she met Frank, they fell in love and were married. Frank stayed with the Czech army for some time-he was told he could even rise to general if he stayed, but he preferred to get out and was demobilized in early 1946. Afterwards he became chief attorney for the Czech chemical industry. But when the Czech Communist party seized power, he was frightened and in 1950 asked for permission to emigrate to Israel. His boss became rather angry-he told Frank, there was no chance he would be allowed to go, since the chemical industry was viewed as having military importance. And of course, he could not keep his job; but the boss liked him and found for him a low-level low-visibility post where he stayed. Frank said that saved his life: important officials were later purged, but he stayed safe. In 1952 a new minister came into office and asked him to assume once more a prominent position. Frank said he would like to be excused because he wasn't a party member, and the answer was "we will find someone to instruct you in Marxism." That "someone" was an old-time worker, appointed to keep an eye on Frank. He turned out to be a decent chap and not only did he create no trouble for him, he even warned him about enemies in the office.

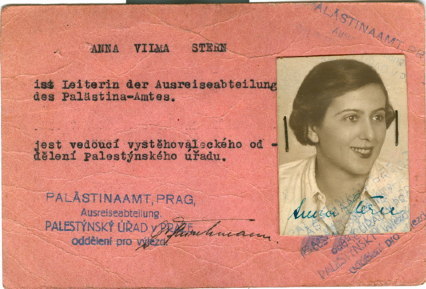

But Frank realized he would no longer be safe and said so to Bella when he got home. Three months later they and their daughter Michelle, age 5, traveled to the border, stayed at a farm house and then, at night, walked across to safety. Michelle was terrified by the experience and a few years later refused to cross even the US-Canada border. But they were safe, stayed for a while in England and then moved to Canada, where they both worked in real estate and prospered. Frank ended up owning a shopping center some 100 miles from Montreal and it provided him with a very comfortable income. Frank's sister Lilly also survived and married Eugene Fleischner of Seattle, Washington. Her daughter Daniella ("Danushka") married a Seattle professor of psychology and raised two sons, also two adopted daughters. Anny SternAmong the Jews trapped in Prague was Minna's daughter Anny Stern. She volunteered to work in the Zionist emigration office there, headed by Jacob ("Yankev") Edelstein, later head of the Jewish community in the concentration camp (aka "ghetto") of Terezin (Theresienstadt). Earlier, when Austria was annexed by Nazi Germany (the "Anschluss"), a similar office in Vienna managed to get many Jews out to British Palestine. However, by 1939 the British authorities had largely blocked that route. The Nazi officer responsible for the emigration office was the notorious Adolf Eichmann, who had also ordered the setting-up of the emigration office in Vienna. As Anny told in a 1977 interview:

"Edelstein came back from seeing Eichmann for the first time and said: "We have to make an immigration office - that means Anni, this is just what you can do, You will put down every day the names of people who want to emigrate, who get visas, who get certificates, and that we give daily to The Gestapo." While we were[later] sitting, about 8 people, all the leaders of the Zionists and the Jews in Prague, a man rushed in, one of the--office guards, or whatever you may call them --and said: "Eichmann and his staff are here" Eichmann: Dr. Stern, are you a Zionist? --My answer: Yes, Herr Obersturmbannführer. Eichmann: I am a Zionist too. I want all Jews to get out as quickly as possible and you have to work hard. So -- one of his questions, one of his first questions, was "who is in charge of the emigration?" As they were not prepared for it, they gave me George's title and said "Mrs. Dr. Stern". So Eichmann took me under oath, that I will be in charge of the emigration, will work with the SS and the Gestapo, and will be absolutely responsible for what I'm doing. And this is how I started my career, never having sat at a desk." In May 1939 Edelstein was allowed to travel to British Palestine to plead with the British for more entry "certificates". He stayed in the country for a week, and friends urged him to remain there, but he felt his duty was in Prague and came back. He and his family were shot in Auschwitz in 1944. To get more people out of the country, beyond the legal trickle, the Zionist organization organized illegal emigration to British Palestine (Edelstein might have coordinated that too, during his visit there). It required an appreciable amount of paperwork, and Anny was one of those handling it. The process had several steps. First, a pro-forma legal exit had to be arranged, by buying fake visas from foreign consulates, usually those of Latin-American countries. The Germans did not allow anyone to leave unless that person had a visa to somewhere. The visas were sold with the unspoken agreement that they would not be honored by the countries that issued them: they were only intended for exit from the Nazi protectorate. As Anny told (1977):

"And this had to have a certain quota. The quota under pressure was 400 a day, otherwise it was 200 a day, which was an enormous load of work to be done… I went to all the consulates, all the embassies in Prague. I got usually - for money, of course - I got visas, 500 visas to Peru or 300 visas to Chile, which could never have been used for an entry to Chile. Our standing joke was "What's the capital of Peru?" and the answer was "Tel Aviv". Or, "What is the capital of Chile?", the answer was "Tel Aviv." This is how we got visas, because every emigration paper had to have a visa. The Germans didn't give you a - "durchlasschein", the paper to leave the country and the possibility [to buy] ship tickets or whatever, if you didn't have a visa. The only country to which you still could go was England, which of course later was closed (when England declared war on Germany, in September 1939)." Second, the government demanded an arbitrary "Reich escape tax", shaking down the migrants for whatever the Gestapo (German acronym, "secret governmental police") could extract. Only then could they legally leave and claim an allocation of foreign exchange to pay for the trip. When Anny arranged for her own exit, the Gestapo viewed her especially valuable, and asked for an unusually large amount. Below is the affidavit by an unnamed witness of what happened, found in the papers left by George Stern. (The original German account is translated here by David Stern, with question marks for uncertain words): "I emigrated from Prague at the end of 1939 and therefore participated in all the procedures associated with emigration, and thus know them from personal experience. Whoever in that time wanted to emigrate to Palestine, was next required to submit at the Palestine office a folder with countless forms and questionnaires. Among these also was a questionnaire dealing with the wealth of the applicant, and in cases where a "Reich-escape-tax" liability existed, the Palestine office also immediately calculated on an attached form, based on these inputs, the Reich-escape-tax, and brought up (?) the payment thereof. Some time after the completion of these preparations and declarations, the affected person was summoned to the central office of the Gestapo in Strechowitz, Here those summoned for the day stood in line. By chance I was summoned to the central office of the Gestapo on the same day in November 1939 as the person asking for this document [this affidavit] Mrs. Anna Stern, who was, by the way, working at the Palestine office and entrusted with the preparation of the folders mentioned above. Mrs. Stern stood in line just ahead of me, and as the line moved from one counter to the next, I stood just behind Mrs. Stern and therefore observed and heard what went on at all the counters. Among the last counters was one where the payment of the special contribution and the Reich-escape-tax were checked. In the case of Mrs. Stern the clerk-as in many other cases-sought out in the folder the form in which the Reich-escape-tax was already figured out, and furthermore sought out the receipt of payment thereof and also found it. I remember that the amount talked about, of a prescribed and already paid Reich-escape-tax, was 400,000 crowns or something more. I remember the number, because it was the highest amount of the Reich-escape-tax of which anyone in our emigration group had heard. With verification that this amount was paid in order, this matter however was not finished. Much more did the Gestapo official chastise the applicant in harsh voice, addressing her as "you Jewess" and demanding an additional payment of 100,000 crowns for the Reich-escape-tax. I still remember well how baffled and hurt the applicant was. A reason for this surcharge was not given. Because the applicant, naturally, did not have this additionally demanded sum, since she was not prepared for this additional demand, she had to leave incomplete things (?) at the Gestapo central office. I am aware that shortly afterwards she actually emigrated, and I conclude from this that she finally found means and ways to raise and pay the additional forced amount of 100,000 crowns. Naturally this case was repeatedly discussed in the entire emigrant group of that time, and it turned out that the applicant was absolutely not the only one who was handled by the Gestapo in the way described here. My ears have heard of an entire series of similar cases, which gave the impression that the extortion-measures (?) in the cases of families, of whom the Gestapo could determine the availability of a certain wealth, formed at that time a deliberate system." In her 1977 interview Anny also mentioned this extra extortion, though she said the amount was 30,000 crowns. After their "tax" was paid and approved by the Gestapo, Jews were permitted leave the occupation area. Those with legal visas to other countries (e.g. "certificates" to enter British Palestine) left by rail and ship, but those having only fake visas traveled to the Slovak capital Bratislava, on the river Danube that leads to the Black Sea in Romania. The Danube was an international waterway, so those refugees could board a river steamer to the Romanian port of Constanza, to worn-out steamships bought by the Zionist organization to run the British blockade. Anny told about it in 1977: "Later the Palestine Office gave me a monthly allowance as well, because I collected an enormous amount of illegal money, hundreds of thousands of Czech crowns which I had hidden in my desk. I had a desk with a kind of secret wall - secret compartment - where I had hidden thousands and thousands and hundred thousands of crowns which I got from all the people I helped. They had "black" money, they couldn't do anything with it, so they gave it to me and I in turn gave it for the payment of illegal transports and illegal ships. We had the Maccabi, for instance (a Jewish sports organization), we worked with the Maccabi who made the illegal transports. We had to buy the captains, we had to buy the ships, we had to buy the visas - we had to buy everything." One source of money was a rich relative of Anny's-Martha Hirsch, daughter of Minna's sister Regina. who married Hugo Rudinger. Willy and Martha owned a wire factory in Czechoslovakia and were quite wealthy: they lived in Pilsen and were friendly with Kokoschka, who painted her picture several times. When the war broke, their son Richard was already living in Australia, but they themselves had to flee to Prague, where they were trapped by the German occupation. Anny was working in the emigration office, and she went to them and told them-"I can get you out, but you have to trust me. " She then went to Yankev Edelstein, told him the Hirsch'es had large sums of money which the organization could use, and made the arrangements. Much of the money of course was taken by the Germans: they appointed a special attorney, Dr. Dewalt, who it turned out had been an intern in George Stern's law office. They got a certificate to Israel and were all their life grateful to Anny--"just when we gave up an angel appeared, in a cape with red lining, and told us 'trust me'." Two years later they made it to Australia. Their daughter Marie Louise lived to age 100, passing away in Australia 8 May 2015. "No, at this time we didn't get any help from the outside. We had a few people who had, for instance, no possibility of leaving, because they were even at that time important, as they were scientists, chemists, whatever. Like before, with the Reichsanrat Uttermoehle, I went to this commercial department of the Gestapo and I got the people out. I had the possibility of getting out people from Dachau and Buchenwald, in the transport. Not too many, but in my ignorance I thought that for money you can actually buy everything, and I did what nobody ever dared to do, I bribed some Gestapo - lower Gestapo officers - and got about 15 people out, or 10 people out here and 3 people out here. And this I did with all the "black" money, which is very deeply engraved in my mind, because I had once a search party from the Gestapo coming into my office and looking through all the desk, if there would be some papers, which they wouldn't know about it, or some secret messages, because we were allowed to speak once a day with Italy, because of illegal boats, and so on. And all the money was in my desk, and the people who came in with Eichmann- that was actually not Eichmann himself, it was one of his adjutants called Lederer, and I don't remember the name of the second one. The second one was one of the guys who came with a submarine to America and was caught here, and was later, I believe, executed. That was one of Eichman's adjutants. Lederer, who looked like a bully, was frightening and had a Jewish name, was actually very decent, he helped wherever he could." The illegal exodus essentially ended when Britain and France entered what became World War II. As Liesl told "…in the autumn of 1940, that was the last ship which went out. I remember two friends of mine, two girl friends of mine, who trained as I for nurses, went to Brünn [Brno], and joined there the whole group, they came to Palestine. But that's been the last, the last, the last to get out.' The last ships to reach British Palestine with Czech refugees were 3 small steamers. Their passengers were denied entry and placed in Haifa aboard the French liner "Patria", to be taken to the island of Mauritius. The Jewish underground "Haganah" tried to stop the transfer by attaching a bomb to the hull of the Patria, meaning to disable it. Unexpectedly, a big hole was torn and the ship sank in 16 minutes, drowning over 200 refugees. Anny continued: "Eichmann went on - when he was in Prague, he left the people and he went on. I was with Eichmann, with himself, maybe two or three times, I don't recall it. I was taken twice as a hostage. They said - they took me and another friend by the name of Erich Munk, a surgeon who was a friend of mine, who had a teaching possibility and the papers to teach in America, as he was a very promising and able young surgeon, who helped me. And we were taken as hostages to the Gestapo, because we didn't fill the quota, we didn't send the right information - these things I really wanted to forget, and by today I have forgotten them. What stays with me was that we were hostages. And it was very simple. You came in, and they said "sit down". They made a little point on the wall with a pencil or with ink, and they said "look at this point and don't move. You move left, you move right, you will be shot." And then they asked us questions. I must say it makes you nervous if you sit like this and I don' t think you can take it much longer than maybe an hour - I couldn't, but I was at this time - how old was I? I think 30. And Erich Munk was about 32, or the same age as me. We were taken hostages about 10 o'clock at night, and stayed there till 11, or we stayed till 12, I don't know any more, and came out on the old marketplace, the Staromestske Naměsti, I wouldn't know how to call it [old town square], in Prague, which is very famous, with the clock and all this. We came out, and there were some friends waiting for us, like Jacob Edelstein, Zucker, Kahn, all very prominent names in the Jewish and Zionist history of Czechoslovakia. We all had special Gestapo passes, so we could walk on the streets. It was a green card, double card, with our picture with a big Hakenkreuz - a big swastika - saying that we are allowed to be out after - I don't know, seven o'clock or eight o'clock in the evening, we didn't have a time limit. They were waiting for us. It was raining, it was cold, and we were pretty much - Erich Munk and myself --I would say on the end of our endurance. And I said to Erich: "We will never survive as people. " I didn't speak of myself or of him as persons. So he said: "You will see, we will survive, we will be great, we will achieve things we don't think we will be able to achieve, and when we have achieved it, we will give the other cheek and they will hit us on the other cheek."